2. History of Kampo Medicine

The term Oriental medicine usually refers to treatment methods such as acupuncture, moxibustion, herbal therapy (Kampo), cupping, and mind–body practices such as Tai Chi and Qi Gong, all of which originated in China and are collectively known as Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM).

In a broader sense, Oriental medicine includes traditional medical systems practiced across Asia, from Turkey eastward — such as Ayurveda in India, Unani medicine in Islamic regions, and traditional Chinese medicine itself.

The Evolution of Japanese Kampo Medicine

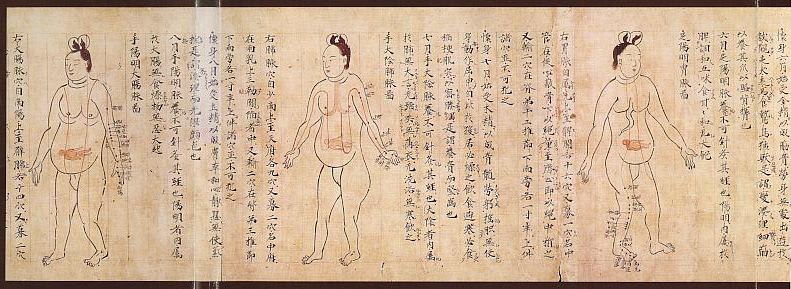

Kampo therapeutic methods were introduced to Japan around the 6th century, during the Han Dynasty (206 BC–220 AD), by a Chinese monk-physician. As part of a cultural exchange, he brought 164 medical texts from China, introducing practices such as herbal medicine, acupuncture, moxibustion (moxa), and massage.

In 701, Kampo medicine was formally recognized under the Ishitsu–Rei (医疾令), a medical regulation enacted by the Japanese government. During the Heian period (794–1192), Japan’s unique culture flourished, and Japanese medicine began to develop its own distinctive features. In 984, the Japanese physician Tamba Yasuyori compiled the Ishinpo (医心方), the oldest surviving medical text in Japan, which systematically summarized the medical knowledge of the time.

During the Kamakura period (1192–1333), the spread of Zen Buddhism reintroduced Chinese medical texts through the Rinzai school of Zen. Physicians, particularly in the city of Hakata, practiced medicine based on Chinese theories.

By the late Muromachi period (15th–16th century), distinct schools of Kampo thought had emerged. Tashiro Sanki (1465–1537) established the Gosei-ha (後世派, Later Generation School), which emphasized empirical study and the use of classical formulas, while other schools focused on theoretical aspects of traditional Chinese medicine.

In the 17th century, during the Edo period, physicians such as Gomyo Tashiro and Goto Konzan further refined Kampo theory. The Later Generation School remained dominant, focusing on disease names and symptomatic treatment. In contrast, the Koho-ha (古方派, Ancient Formula School) revived the classical principles of the Han dynasty, basing diagnosis and therapy strictly on canonical texts such as the Shanghan Lun (傷寒論, Treatise on Cold Damage) and the Jingui Yaolue (金匱要略, Essential Prescriptions from the Golden Cabinet).

As time passed, debates between these schools gave rise to a reformist movement known as the Setchu-ha (折衷派, Eclectic School), represented by figures such as Hanaoka Seishu, who sought to reconcile empirical observation with classical theory.

In 1635, Japan implemented the Sakoku Edict (鎖国令), closing its borders and restricting foreign contact for over 200 years. This period of isolation allowed Kampo medicine to evolve independently and become deeply rooted in Japanese medical practice. When Japan reopened its borders in the mid-19th century, Kampo medicine coexisted with Western medicine and continued to play a significant role in healthcare.

During the Meiji period (1868–1912), Western medicine was officially adopted as Japan’s national medical system, and Kampo medicine was largely excluded from formal education. However, interest in Kampo was revived during the Showa period (1926–1989), leading to renewed academic research and clinical application.

In 1967, Kampo extract formulations were approved for coverage under the National Health Insurance system, allowing Kampo medicines to be prescribed in modern medical practice. Today, it is estimated that nearly 90% of Japanese physicians have prescribed Kampo medicines at least once in their clinical careers.

Behind the name of “Kampo” Medicine

The term Kampo medicine originates from the Chinese characters “Kan” (漢) and “Po” (方). The character “Kan” refers to the Han dynasty (206 BC–220 AD) in China, a period that greatly influenced the development of traditional Chinese medicine. The character “Po” means “method,” “formula,” or “prescription.”

During the Tang dynasty (618–907 AD), two foundational medical texts — the Shang Han Lun (Treatise on Cold Damage) and the Jingui Yaolue (Essential Prescriptions from the Golden Cabinet) — were compiled. These works became the cornerstone of traditional Chinese herbal medicine and formula-based therapeutic systems.

When these medical traditions were introduced to Japan, they came to be known as “Kampo” (漢方), meaning “Han method” or “Han formula.” Over time, the pronunciation evolved into Kampo in Japanese.